Milkmaids and milkmates from Ecuador to Estonia have been getting after me to refocus this blog on the Men of Milk. You were mildly amused when I assumed the role of musicologist, studiously analyzing the merits and warts of more commercially successful bands—but that's not really what drew you to themilkmen.space in the first place or what's kept you coming back for more.

Let me take a wild guess what you've missed most: it wouldn't happen to be more shameless self-promotion, would it? You know, those chatty missives hyping us as one of the greatest undiscovered bands of all time and yours truly as the top dual-threat songwriter/prosewriter extant?

Message received! And it's certainly true that historically I've relished my role as resident hypemeister. I would have been happy to continue in that vein, but 2021 wasn’t exactly a banner year in Dairyland. It’s hard to crow about achievements or accomplishments ... when there weren’t any. Our lack of production was, er, humbling, to say the least. If that wasn’t humbling enough, I had to contend with becoming a septuagenarian—a septuagenarian finally forced to face the devastating reality that the band nearest and dearest to my heart may never receive the plaudits for our long-term output that we garnered nonstop when we broke so briskly out of the gate. That never stopped me from producing one recognition-worthy tune after another, until, uncharacteristically, I sulked my way through 2021.

I'm already unsulking in 2022, chewing the cud and weighing the canniest ways to reconnect our fanbase with the mother teat. Come to think of it, there’s a compelling tale I’ve held in reserve that addresses a vexing question I’ve deflected for the better part of forty years: how on earth did we ever find the funds to keep churning out topnotch tunes over seven decades without selling umpteen million recordings and stadium seats—like every other band that's survived anywhere near that long’s had to do?

“Desire” is the one-word answer.

Fine, but the money to alchemize desire into “product” had to come from somewhere. In our case, monolithic conglomerates like Apple, IBM, Intel, Century Link, and Safeco Insurance all (inadvertently) pitched in, not to mention even stranger bedfellows like Marijuana, Inc., and no less a facilitator of our dairy dreams than the freakin' United States Treasury Department by order of the Department of Labor!

Hooking up with these deep-pocketed benefactors must have taken us years and years of high-level planning and tense negotiations to pull off, right? Nope. It was all serendipitous—though par for the course, when you pause to consider the peculiar script my "inside-out life” has followed. You see, whenever I’ve made concerted attempts to monetize my artistic efforts, I’ve usually failed miserably; on the other hand, I’ve been on the receiving end of one startling windfall after another, allowing me to keep expanding my songwriting Silo of Hits and my prose writing portfolio. If I sit in a lotus position, I can see those out-of-the-blue cash infusions as some form of karmic recalibration, arranged by a benevolent universe, compensation for the Herculean effort I've poured into creative projects that's rarely been rewarded through conventional means.

But I'm getting ahead of myself. Back in the days of Milk Crusade I (1979-1985), there actually was a plan in place, masterminded to rocket us to the outer stratospheres of superstardom. It was simplicity itself: soliciting and receiving support from the most obvious player—the dairy industry.

But I'm getting ahead of myself. Back in the days of Milk Crusade I (1979-1985), there actually was a plan in place, masterminded to rocket us to the outer stratospheres of superstardom. It was simplicity itself: soliciting and receiving support from the most obvious player—the dairy industry.

That was the intention, anyway. I saw it all, in vivid detail, right from Day One in 1979 when I stumbled out into a frigid early morning mist after an all-night recording session in a Table Mesa suburb. As yet unidentified crunchy sounds preceded the emergence of a milk truck swinging onto an icy driveway. The grand scheme was already formulating in my mind, even as I watched a uniformed milkman hop out of his snub-nosed conveyance, jiggling milkstuffs in a bottle carrier, striding purposefully toward a Watts-Hardy Dairy milk box. By the time he'd gingerly arranged an assortment of lactose-based staples and retraced his steps, the whole milking schtick had crystallized in my mind: our name would be The Milkmen, our stage show would feature a robotic bovine, and our uniforms would be adorned with patches proclaiming our proud sponsors in the dairy industry, just like racecar drivers' uniforms are speckled with patches advertising their backers in the oil and gas racket. It was, bar none, the best idea I've ever had. I get all tingly just thinking about it.

Alas, this noble ambition never evolved beyond two dozen stenciled milk boxes gifted by Boulder’s Watts-Hardy Dairy. I’ve cried in my milk over our (okay, my) failure to execute that game plan more times than I care to admit.

Boulder's lamentably defunct Watts-Hardy Dairy was reconstituted into the Dairy Arts Center.

Inability to ally with the dairy industry could have spelled disaster for our fledgling enterprise if the milk gods hadn't been looking out for us—in the most roundabout ways imaginable. If The National Enquirer wrote a headline about it, it would be : “Fortune 100 Companies Paid Me $300,000 Not to Write!”

That's just a little taste.

But first there was ...

Marijuana, Inc.

The entirety of Milk Crusade I (1979-1985) was bankrolled through selling metric tons of "the magical herb." Everything from our guitar picks to our outlandish costumes and stage set to Bessie the Cow was purchased with proceeds generated from these “ill-gotten gains.”

Oh, wait, tell a lie: “Lolita,” the song that won the 1981 KBCO Songwriting Contest, jumpstarting our career in the process, was incubated in a private fantasy studio literally built into the rocks above Left Hand Canyon. A pad and a half like that existed because its foosball-loving owner was the brains behind conceiving, manufacturing, and distributing millions of doses of Mr. Natural blotter acid (LSD)—an all-time great product worthy of enshrinement in the Hallucinogens Hall of Fame. To be precise, Acid, Inc. paid for the studio itself—which offered us weeks and weeks of free time to come in and put the radically-designed room through its paces—while Marijuana, Inc. picked up the tab for everything else, including an engineer, a studio musician like Ric Parnell, who'd later become immortal as Spinal Tap's expoding drummer, and prepping and pressing a single.

Back in the day, gigs like New Wave Mondays at Boulder’s Blue Note Club actually paid us really well—but not nearly well enough to afford extravagances like flying Parnell and his redheaded “bird” Cindy out from LA to play one gig. If you didn’t fly her out too, well, then her “old man” would go on a coke binge and wind up playing the snare drum with his head at sold-out shows we'd have to end early, pissing off everyone in the club who was worshipping us like the second coming moments earlier.

In the early 1980s, the commodity with that sort of purchasing power was usually reddish-golden Colombian weed, pressed into 20-50 pound bales in South America, exported to Florida by plane or boat, then overlanded to key distribution points like Boulder/Denver in recreational vehicles, typically Winnebagos, or "Winnies" as they were affectionately called. Despite the presence of unsmokable stems and seeds rarely encountered in today’s meticulously groomed sinsemilla strains, a $35 ounce of Colombian was affordable enough, tasty enough, and effective enough to keep your average stoner blissed out for weeks, if not months.

If you were well-connected, like I was after a few years of dependable service, you could buy a pound of Colombian for roughly $300 in 1980 money. There are sixteen ounces to a pound. Selling 9 ounces for around $35 each—which invariably “flew off the shelves”—left seven ounces of pure profit. In other words, buy for $300, sell for $560, make $260—which came in handy back in the day when $600/month rents for decked-out, mountain-view two-bedroom condos were commonplace and dinner for two with a decent red at the swank Flagstaff House looking out over the plains all the way to Kansas cost $75. That was the retail market in a nutshell.

Before long, I graduated into wholesaling, marking up each pound $20 or so. That translated to a quick $1,000 killing on a 50-pound bale ($20 x 50 = $1,000). When things were rolling, I’d sell more enterprising customers three bales at a time and pocket $3,000 for an afternoon exchange.

There was also the option of selling a certain amount of individual pounds out of every bale, at, say, $50 profit per, and wholesaling the rest. There were unlimited ways to win at the outlaw pot game (and some ways to lose, too, as we'll find out).

There was also the option of selling a certain amount of individual pounds out of every bale, at, say, $50 profit per, and wholesaling the rest. There were unlimited ways to win at the outlaw pot game (and some ways to lose, too, as we'll find out).

Eventually, I seized upon the most creative of them all: manifesting a pound of weed out of thin air! How exactly does that work? A pound is 454 grams. I’d take a bunch of bales, spread them out all over my living room’s orange shag carpet as was my custom, and divvy the lot up into one-pound Ziploc freezer bags. Then, I’d reach into each bag, carefully extract precisely one gram from each bag—according to a dead-accurate Ohaus triple beam balance scale—and place it inside a “special” bag. In a couple of weeks, that special bag would swell in one-gram increments until it reached 454 grams.

Voila—that's how you summon something from nothing! Only the something was now worth at least 400 bucks. Back then, you could buy a pretty decent guitar or amp for $400 … or hire a seamstress to design, fabricate and customize Milkmen unis … or start saving up for a synth … or pay a soundman’s salary for three or four gigs … and so on. I could get away with doing that because everyone knew that weed dries out over time. Minor amounts of shrinkage were accepted as an occupational hazard; no one had any problems with pounds that were 99.77% intact.

Another avenue for monetization opened up: “the transport sector,” driving cars and recreational vehicles between south Florida and Boulder. Piloting a Winnie crammed to the gills with the devil’s weed through bible belt states where they regularly locked guys up and threw away the key for interstate transport came with a commensurate amount of pressure—and commensurate compensation, around $7,000 per round trip. That’s $7,000 each for you and the babe selected to pose as your better half seeing the USA on a road trip. Then full-size car routes to less perilous locales like Pittsburgh opened up; the Boulder-Pittsburgh route was a relative breeze. That paid roughly $3,000 for the round trip, plus expenses, for four days’ work, when the weekly personal income per capita in the United States averaged $200—before taxes. Not bad!

At my intermediate level in Marijuana, Inc., the lifestyle was ideal. I was deep enough into it that I thought nothing of plunking down cash on the barrelhead for a new Toyota Corolla hatchback, but not in so deep that I had to deal with the risks and logistics of importing a skunky, bulky substance into the country. My “co-conspirators” consisted of a few college buddies that I'd stayed in touch with and friends of those friends; I never once saw a Colombian or a gun (much less a chainsaw!) during the decade I thrived as a purveyor of outlaw pot. Looking back over my checkered career, I'd have to say that outside of my highest calling—lead singer for The Milkmen—saleshuman in the cannabis trade is the position I've been most suited for.

In 1989, two factors brought this reddish-golden era to a climactic denouement: several of my "associates" were busted and “went away,” and my daughter, Isabelle, popped out. Her tiny helpless protoplasm was way too cute to contemplate not being around. Clearly, the smart move was quitting while I was ahead, exactly what I did.

The Transition Phase

You might suppose that "professional life' couldn’t get a whole lot more off-the-wall than playing a space-milkman heaving bucketsful of lactose into a pulsating crowd—or being cast as half a husband/wife team maneuvering weed-laden Winnies through redneck Georgia—but supposedly stolid, sober Corporate America stages some sneakily great Theater of the Absurd.

Take, for instance, the drama at one of my first corporate stops, a quick two-week PC-support stint at Telecommunications, Inc., or as John Malone, “the king of cable television," initialed it, TCI. IT had me scampering all over their Denver Tech Center towers, setting up PCs, installing software, swapping out blown CRT monitors, and so on. One day I was tasked with installing Microsoft Office—which, in 1992, came on 25 floppy disks which took an hour and a half to install—on a high-ranking exec's PC.

The most provocative station in TCI's lineup had to be The Spice Channel, a treasure trove of softcore porn. That's the channel this exec left on for my viewing pleasure, one man of the world to another, while he took off for lunch. It had the desired effect: Emmannuelle 2 minimized the drudgery and really made time fly, very considerate of him. Anyway, somewhere around the 14th disk mark, I called my wife on the office phone, thinking nothing of it. To make a long story short, the same guy who’d directed me to watch porn on his personal TV had me axed for having "the audacity" to use his personal phone! Okay, then.

Speaking of phones, my punishment for being summarily dismissed by TCI for pawing one was finding my salary doubled at my next stop, communications colossus US West (later Qwest and now Century Link), “the phone company” for fourteen western states. I reported to their facility in the Denver Tech Center, all bright-eyed and bushy tailed, ready to show the world what this PC Support Specialist was really made of. Aside from the fact that the same supervisor who'd hired me on a Friday was no longer working there by the time I showed up the following Monday, one small hang-up kept me from making the positive impression I had in mind: it took the phone company, which had brought me on for “phone support,” six weeks to bring me a phone!

Speaking of phones, my punishment for being summarily dismissed by TCI for pawing one was finding my salary doubled at my next stop, communications colossus US West (later Qwest and now Century Link), “the phone company” for fourteen western states. I reported to their facility in the Denver Tech Center, all bright-eyed and bushy tailed, ready to show the world what this PC Support Specialist was really made of. Aside from the fact that the same supervisor who'd hired me on a Friday was no longer working there by the time I showed up the following Monday, one small hang-up kept me from making the positive impression I had in mind: it took the phone company, which had brought me on for “phone support,” six weeks to bring me a phone!

When a phone eventually materialized, naturally I anticipated that the dead zone otherwise known as my cubicle would instantaneously transform into a hotbed of activity. Think again! I began receiving maybe one 13-second phone call every three days or so, more often than not from some confused linesman in Idaho or South Dakota, who’d shinnied up a telephone pole and dialed the wrong support number in a blizzard.

I was still without a computer, that was a bridge too far for the US West IT Department. When soul sister Sharon, an inner-city black supervisor intent on proving women of color could excel in the workplace (which by then had already been proven beyond any reasonable doubt innumerable times) tapped me, of all people, to sort out some imagined life and death crisis requiring the immediate use of a working PC, she issued an executive order to march right over and use the department manager’s.

Once bitten twice shy, I was feeling more than a little squeamish about the possible repercussions of carrying out what amounted to a suicide mission. Big Paul, the heavyset leader-of-men this early Dell machine belonged to, was one surly dude. He’d given us underlings, er, “motivational talks,” informing us that he’d warned his own wife that if she ever failed to carry out his bidding, he’d “bone her like a fish,” so imagine what he’d do to us. Oh. Of course we'd have all have run through brick walls for him after hearing that ... that is, right after we all got done throwing up in our own mouths. Anyhow, I’d barely begun untangling this supposed crisis on the department manager's PC when I caught a glimpse of his stocky frame huffing and puffing my way. Uh-oh. Drawing closer, Big Paul's cool, calm, and collected mien morphed into a sinister scowl. Looming behind me, he stared intently, pupils dilating, eyebrows lifting, before bellowing, “I feel so violated!”

And here I was thinking musicians were the world’s biggest prima donnas!

Until it was so rudely interrupted, that was my first taste of sitting in a cubicle all day long doing absolutely nothing while getting paid absolutely everything. I figured that had to be an anomaly in Corporate America; boy, did I figure wrong! You might think I’d never work at US West again after committing yet another unpardonable workplace faux pas, but you’d think wrong—not only did an organization entrusted with the care and maintenance of a communications network stretching from Santa Fe to Sioux City hire me again, it hired me again twice!

Perhaps you're wondering how someone without a corporate bone in his body wound up working for one Fortune 100 company after another? Curiously, love of music paved the way. In the late 1980s, with The Milkmen down and possibly out, I wanted to keep playing in a band context—only there weren’t any analog beings in my immediate orbit I was psyched to play with. As luck would have it, this was the exact point in time and space when digital bandmates became a thing. Not only were they a thing, but I already had them at my disposal. One of the better purchases I’d made with my filthy Marijuana Inc. lucre was a now-mythic Oberheim System. The cutting-edge trio consisted of an OB8 synthesizer, a DMX drum machine, and a DSX sequencer. Hardware sequencers like the DSX could simulate an entire band by recording passages of notes played on synthesizers and drum machines, layering various sounds from bass through brass together, then playing them all back with your timing imperfections corrected.

Perhaps you're wondering how someone without a corporate bone in his body wound up working for one Fortune 100 company after another? Curiously, love of music paved the way. In the late 1980s, with The Milkmen down and possibly out, I wanted to keep playing in a band context—only there weren’t any analog beings in my immediate orbit I was psyched to play with. As luck would have it, this was the exact point in time and space when digital bandmates became a thing. Not only were they a thing, but I already had them at my disposal. One of the better purchases I’d made with my filthy Marijuana Inc. lucre was a now-mythic Oberheim System. The cutting-edge trio consisted of an OB8 synthesizer, a DMX drum machine, and a DSX sequencer. Hardware sequencers like the DSX could simulate an entire band by recording passages of notes played on synthesizers and drum machines, layering various sounds from bass through brass together, then playing them all back with your timing imperfections corrected.

That was empowering enough, but right on their heels came software sequencers, designed to exploit the new MIDI protocol. That was a big deal because not only could PCs perform more complex sequencing feats than hardware sequencers, they could display a full screen's worth of information to boot. An endearing little Mac SE running Mastertracks Pro replaced the DSX as the brains of my outfit, expanded to include Yamaha DX7 and Roland D50 synthesizers, and a Yamaha Rev 7 rackmount reverb. Now I could compete with commercial studios in the privacy of my own home, without forking over hefty hourly rates for studio time—or I could provided I had the time and patience to demystify how all the components worked individually and collectively, with minimal help from manuals written in inscrutable "Japo-Saxon." In the advent of the digital age, when online user forums were just becoming a thing, unraveling the vagaries of electronic gear out was no small feat.

That was empowering enough, but right on their heels came software sequencers, designed to exploit the new MIDI protocol. That was a big deal because not only could PCs perform more complex sequencing feats than hardware sequencers, they could display a full screen's worth of information to boot. An endearing little Mac SE running Mastertracks Pro replaced the DSX as the brains of my outfit, expanded to include Yamaha DX7 and Roland D50 synthesizers, and a Yamaha Rev 7 rackmount reverb. Now I could compete with commercial studios in the privacy of my own home, without forking over hefty hourly rates for studio time—or I could provided I had the time and patience to demystify how all the components worked individually and collectively, with minimal help from manuals written in inscrutable "Japo-Saxon." In the advent of the digital age, when online user forums were just becoming a thing, unraveling the vagaries of electronic gear out was no small feat.

Some PCs, more often than not Macs, showed an aptitude, if you will, for creative pursuits, though by and large the vast majority of bland, beige boxes churned out by the likes of IBM and Compaq wound up on the desks of corporate drones, designated for bread and butter tasks like word processing and spreadsheets.

In the dawn of "the dotcom" era, business sections of "great metropolitan newspapers" began running articles about the wonders of computer networking, where a server PC—programmed by and attended to by highly-compensated network gurus with arcane knowledge of router tables, mainframes, and communications protocols—controlled anywhere from a few to a few thousand PCs. It occurred to me that was pretty much what I was already doing with my music setup, and, hey, I could get paid to do this.

But no one becomes a highly-compensated network guru without first familiarizing themselves with the nuts and bolts of PCs. And so it came to pass that at the age of 40, I sucked it up, enrolled in the PC Support Specialist program at Votech in Boulder, and, a few seasons of relatively intense labwork later, officially became one. After I posted a, shall we say, somewhat fictionalized resumé on nascent job search sites dice.com and monster.com, high-tech recruiters seemed impressed with the fresh educational credit. Didn't Hall and Oates raise their voices in song about the joys of "Adult Education?"

Before I knew it, I was fulfilling temporary "contracts" for employers who needed to bring someone on, but either didn't want to go through all the rigamarole of hiring full-time employees or liked the idea of a no-commitment trial period to see how you worked out. Meanwhile, I'd enrolled in night school at Red Rocks Community College in Golden (not far from world-renowned Red Rocks Ampitheater), on the fast-track to becoming a Certified Network Engineer.

Making the grade as a CNE involved passing a trickily-worded series of multiple-choice tests—and, curiously, no lab work whatsoever. After a few near misses, I eventually passed those by the skin of my teeth. However, just like passing law exams doesn’t automatically make someone the terror of a courtroom, just because I happened to have passed some written tests on the third try didn’t mean I was anywhere near ready to run a mission-critical network serving some 35 million customers. That didn’t stop the business entity which had just switched names from US West to Qwest from hiring me to do precisely that!

In fairness to the name-challenged utility, being completely unprepared to run a network didn’t mean it didn’t look like for all the world that, certificate in hand, I was ready to run a network, or sound like I was ready to run a network at interviews I aced—primarily because I had so much practice entertaining reporters who'd asked me everything under the sun about The Milkmen. Sure, I was well-spoken, at least in comparison with tongue-tied engineering types unaccustomed to dummying things down for laymen. That's why some genius thought I'd make an ideal personal network guru for Chairman Joe Nacchio and the rest of the Qwest cabal; that bunch was in the final stages of transforming a $34 blue chip stock into a 34¢ penny stock, from the vantage point of their plush executive aerie atop the 44-story Qwest tower at 1801 California, Denver.

That logic behind that move may have made sense at the time, but, in my heart of hearts, I knew bombing out as a network administrator was just a matter of time. While it was inevitable, it still took a while, since, unbeknownst to me or anyone else at the time, Nacchio and cohorts were only days away from being busted for securities fraud. After the FBI yellow-taped off the 44th floor in a showy raid, business activity at Qwest ground to a standstill. The resulting brouhaha provided momentary cover, delaying my "outing"—but not before the fateful day toward the end of my tenure that, with nothing more pressing on my calendar than exploring the bowels of a skyscraper, I meandered into the Technical Writing Department.

This newly discovered department momentarily threw me for a loop. I had no idea that it existed, or what a technical writer even was. The name implied an individual blessed with perfect left-brain and right-brain symmetry, someone who only had to be technical half the time— which sounded like an immense relief—while the other half of their time, they followed in the footsteps of Ernest Hemingway and Jane Austen, though perhaps that's over-romanticizing the imagery.

In any event, I counted five such beings manning their stations in their obscure corner of a lower floor. One of them was composing ad copy for a flyer publicizing a forthcoming company picnic, earmarked for conspicuous posting in the cafeteria and break rooms. Huh. I was imagining something more along the lines of user manuals. Corporations actually paid these souls to document condiments, cold cuts and cole slaw? Like, really? My jaw dropped. My head tilted to the side. Ding! I think they call that a eureka moment.

I immediately inquired whether the department needed any help—they did! Apparently, tech writers were in demand. Promising. Enough so that I updated my resumé with actual non-fictitious experience, placed the beefed-up version on job sites, and prepared to field calls from headhunters. I didn't have long to wait. Wouldn't you know it, one of the first ones to get in touch claimed to have an in with the main Qwest tech writing group.

Nah—there was no way the battered telecom was going to allow the likes of me inside another one of their extensive downtown Denver commercial real estate holdings—was there? Oh, yeah, there was! And not only did Qwest bump my salary and print me out another ID card, but they were gracious enough to set me up in a dream cubicle overlooking Larimer Square!

Qwest

You may have heard of government programs that pay farmers not to farm. Would it stun you to learn that corporations pay writers not to write? Not only was yours truly one of them, I may have cashed in more for writing less than anyone who ever strode the corridors of industry. It was fitting that I took the first steps toward earning (well, making) a six-figure income under the aegis of the same Rocky Mountain utility that had already sent me packing ... twice.

When I learned that I was under consideration for a third stint with Qwest, I figured there was no possible way the troubled utility could outdo the Daliesque Theater of the Absurd productions it had already put on for my benefit. I severely underestimated them!

The surreal nature of human resources, Qwest style, was in evidence as early as the initial interview. A crack committee of lifers described the caliber of character they were seeking to hire—nothing less than a walking-talking combination of Shakespeare and Edison. Whoever landed the job would have to think like the inventor and write “release notes” like the bard. This Übermensch would also need a good working knowledge of Unix, an operating system I was about as fluent in as ancient Etruscan. I’d digested a morsel or two of it in computer school, which I leveraged by typing the four-letter word in the Relative Skills section of my resumé. Those four innocuous characters landed me the job.

I learned that the release notes I’d be compiling would theoretically be read by systems administrators at various satellite POTS (plain old telephone service) line installations scattered throughout the vast American West. What these systems administrators administered, holed up in outlier locales like Truth or Consequences, NM, were the desktop environments of customer service reps (CSRs, aka ”operators”). The issue was these CSRs had to login to way too many slow-loading mainframe programs in order to carry out basic tasks like adding services, handling billing inquiries, and so on. The halting process took a good fifteen minutes to complete and required advanced improvisational skills, which not too many operators possessed, in the event the creaking system went down during a call, as it was wont to do.

A new system was under development that would automate and accelerate this awkward series of procedures, rendering the old system obsolete in the process. Until it was up and running, the division I was assigned to was expected to keep issuing one or two-page bulletins describing minor patches that could be applied as needed, in order to keep the antiquated system chugging along. The computer language the patches were written in was the aforementioned Unix.

The specific tech writing feat which supposedly required familiarity with it turned out to be nothing more than cutting and pasting a couple of sentences’ worth of command lines from one document to another—without having to grasp what a single syllable meant. I kid you not when I swear that my fourth-grade daughter could have performed the same operation just as efficiently. Even if I'd slammed twelve shots of Tequila and took a handful of horse tranquilizers, it still wouldn't have taken me any more than fifteen minutes to tweak the release notes into an intelligible state. The first month or so into my contract, the pattern seemed to be that these bulletins had to go out maybe once or twice a week.

So, once again, I had next to nothing (constructive) to do at Qwest, which gave me all the time in the world to notice that my absolutely fabulous cubicle at 1475 Lawrence Street boasted an operable glass door, providing easy access to a patio overlooking the sights and sounds of Larimer Square, downtown Denver's most bustling block. Not too shabby! I spent a good portion of the day bathed in actual sunlight, as opposed to mind-numbing fluorescents, free to take girl-watching breaks whenever necessary. When you're the only human on the third floor not actually working, that was pretty often. And those breaks became even more habitual, once I realized that our division was being phased out, fewer and fewer release notes needed to be readied, and no one was really minding the store.

But how many girls could I watch? And how many rays could I catch? What was I supposed to do with myself the rest of the time?

But how many girls could I watch? And how many rays could I catch? What was I supposed to do with myself the rest of the time?

Well, at the start of my third and last stint at Qwest, there was the occasional tête à tête with Jerry Jackson, our doomed division's department head, who'd send for me whenever he required my not-so-special talents to touch-up release notes about arcane software—which no self-respecting field engineer would ever read, since every last one of them regarded consulting them as a sign of weakness. He’d dispatch one of his attractive software testers to fetch me from my cubicle or the patio, depending on where I happened to be exulting in the present moment. Barb or Shiela would present themselves at my cubicle, give me a wink and a nod, then beckon with an index finger. That was the call to arms—“writing” services were required. I was to follow one of them through the security labyrinth and into the formidable server room, where Jerry held sway.

Most server rooms are sterile, EMF-ridden, windowless spaces you wouldn’t want to spend a second in more than you absolutely had to. Our server room had an imposing array of floor-to-ceiling windows, framing epic views of the Front Range and the downtown Denver skyline. Stylish ergonomic chairs that looked like they belonged on the flight deck of the Starship Enterprise added to the designer chic. In a random universe, the low-level background hum emitted by an entire floor's worth of fans, hard disks and power supplies felt somehow reassuring.

After the first few forgettable forays inside this high-tech haven, I settled into my real role on "the team"—a role for which I was, indeed, invaluable. I’d noticed the existence of a Nerf basketball hoop hanging off a Herman Miller overhead storage bin in Jerry's command center. The toy apparatus was somewhat of an anomaly; it hadn’t been in use during my initial visits—or before Jerry had a chance to size me up. But now he was casually squishing a Styrofoam ball in the palm of his right hand ... shooting the breeze about what was up with the Broncos or some forthcoming concert at Red Rocks … nonchalantly tossing the porous orange orb a few feet into the air … then taking aim and firing. Swish! He threw me the ball. I too fondled it for a few seconds, getting a feel for the heft and the distance, then swished it myself. He threw it to me again and again. I swished it again and again, from further out each time. I was accurate, too! Jerry was elated—finally, he’d found someone in the department who could give him some real competition! My status in the sanctum sanctorum of the Qwest empire shot up exponentially, along with the frequency of my appearances.

After the first few forgettable forays inside this high-tech haven, I settled into my real role on "the team"—a role for which I was, indeed, invaluable. I’d noticed the existence of a Nerf basketball hoop hanging off a Herman Miller overhead storage bin in Jerry's command center. The toy apparatus was somewhat of an anomaly; it hadn’t been in use during my initial visits—or before Jerry had a chance to size me up. But now he was casually squishing a Styrofoam ball in the palm of his right hand ... shooting the breeze about what was up with the Broncos or some forthcoming concert at Red Rocks … nonchalantly tossing the porous orange orb a few feet into the air … then taking aim and firing. Swish! He threw me the ball. I too fondled it for a few seconds, getting a feel for the heft and the distance, then swished it myself. He threw it to me again and again. I swished it again and again, from further out each time. I was accurate, too! Jerry was elated—finally, he’d found someone in the department who could give him some real competition! My status in the sanctum sanctorum of the Qwest empire shot up exponentially, along with the frequency of my appearances.

Now Barb and Shiela were sidling up to my cubicle several times a day. If that wasn't enough, shortly thereafter I received security clearance to come and go as I pleased into a highly-sensitive nerve center, where an errant Nerf ball landing on the wrong switch could cripple phone service across a fourteen-state grid.

At that point, Qwest was showering $30/hr. (equivalent of $65/hr. in 2022) on their rookie tech writer to contest game after game of Nerf basketball on a court with a view to die for. Duking it out with Terry in a simulated playoff series gave me the illusion I was a professional athlete, which, for all intents and purposes, I was, for a good six months. Over the forthcoming weeks and months, any business need to pretend that release notes mattered anymore vanished. A live-and-let-live policy was in force throughout the doomed department.

“Fifteen-minute breaks” became hour-long departures spent sampling single-origin coffees or indulging in the art of the sandwich across the street at City Market.

“Lunch-hour” turned into two-hour plus explorations of the many stimulating amenities and attractions that had sprung up all around Larimer Square. I’d try on retro western wear at Rockmount Ranchwear or check out the latest trekking gear at Patagonia. Overland Sheepskin Company stocked some sumptuous pelts.

“Lunch-hour” turned into two-hour plus explorations of the many stimulating amenities and attractions that had sprung up all around Larimer Square. I’d try on retro western wear at Rockmount Ranchwear or check out the latest trekking gear at Patagonia. Overland Sheepskin Company stocked some sumptuous pelts.

As I recount these retail ramblings on Qwest's dime, it should be noted that the general public wasn't completely unaware that things had become a trifle, um, shall we say, unstable over at Qwest. Not only had its stock taken a nosedive, wiping out the retirement funds of loyal employees and the brokerage accounts of conservative investors who'd been looking for a safe play and lost their shirts instead, but it had also been widely reported that the publicly-traded utility was now billions of dollars in debt.

As I recount these retail ramblings on Qwest's dime, it should be noted that the general public wasn't completely unaware that things had become a trifle, um, shall we say, unstable over at Qwest. Not only had its stock taken a nosedive, wiping out the retirement funds of loyal employees and the brokerage accounts of conservative investors who'd been looking for a safe play and lost their shirts instead, but it had also been widely reported that the publicly-traded utility was now billions of dollars in debt.

So, how does a “phone company”—which collected an average of $75 a month from every home in a 14-state area, in pre-cellphone days when everybody absolutely had to have a landline and charges for long-distance were exorbitant; before you even figure in the immense revenue stream that flowed in from business customers—manage to get itself tens of billions of dollars in debt? Wouldn’t Qwest have had to make a concerted effort to fail that miserably, when it had a monopoly and a mandate to collect all those proceeds each and every month? Not when you’re paying guys and gals $60,000+ a year to play Nerf basketball in server rooms! And, don’t forget, contract workers’ agencies got paid really well, too, almost as well as we did. The split was 60-40, so they raked in $40,000/yr. from Qwest, too.

Many dollars banked and clutch baskets sunk later, Qwest finally pulled the plug on our terminal division. There was some real talk of keeping me on—assigning me to the new division tasked with automating CSR logins seemed like a natural progression. That probably would have gone down, or it would have if I hadn’t become infected by the laissez faire attitude running rampant inside the condemned division I was assigned to—which wasn't necessarily the case with other divisions, in particular the tech writing division I was actually employed by. Specifically, it hadn’t spread to the hall-monitor type with access to the same industrial office copier I’d commandeered to print early drafts of Dick, a detective novel I’d been plotting to keep myself occupied. I must have printed thousands and thousands of pages of drafts before this exec caught me red-handed. For some reason, she took offense at my use of company copiers to produce the great American novel. Imagine that!

The copier incident sealed my fate at the hemorrhaging telecom, but not before I’d built up quite a nice little war chest. I could afford to take some time off, continue working on the novel, and prep the songs I anticipated recording for our comeback CD, Dairy Aire. Dick and Dairy Aire wouldn’t have turned out a tenth as well as they did without the generosity of Qwest, the first of many inadvertent angel investors who came to the aid of Los Lecheros (as we're known in Lima) in our hour of need.

Apple

The transactional relationship I had with Apple when I worked for them as a MIDI music demonstrator in 1992—getting paid exactly what I actually deserved to be paid for the actual effort I made—was a rarity, a one-time exception, when the stars aligned and my financial life didn’t feel twisted inside-out. There’s nothing to satirize here; the tragicomic adventures don’t write themselves like they did at every other corporate way station I stopped off at.

I'm not going into depth about the Apple show for a simple reason: it was the antithesis of all the Theater of the Absurd productions I had a front row seat for at all my other corporate gigs; it was more like a well-rehearsed musical. When I tease the headline that “Fortune 100 Companies Paid me $300,000 Not to Write,” those of you who own Apple stock will be relieved to know the i-nnovative Cupertino company wasn’t one of them!

I'm not going into depth about the Apple show for a simple reason: it was the antithesis of all the Theater of the Absurd productions I had a front row seat for at all my other corporate gigs; it was more like a well-rehearsed musical. When I tease the headline that “Fortune 100 Companies Paid me $300,000 Not to Write,” those of you who own Apple stock will be relieved to know the i-nnovative Cupertino company wasn’t one of them!

I bring up my time at Apple because:

- Apple not only paid me to write marketing copy, they also compensated me really well to compose original music! I spent months writing and refining an hour-long demonstration they rolled out at a highly publicized, well-attended, white-tie catered function at their swank 17th floor digs at the Denver Tech Center.

- It’s noteworthy that in an era (early 1990s) when Apple and IBM were going at each other’s throats like King Kong vs. Godzilla, Apple focused on shaping public opinion that original thinkers, creatives, and the truly hip used Macs, while dull, boring, conservative drones settled for IBM PCs. That’s the exact same brainwashing meted out by my local Mac User’s Club as well. Well, the reality was that every last male I saw at Apple wore a three-piece banker's suit, while the supposedly staid IBM workers (I'd find out shortly) went "casual Friday" every day, in golf shirts.

- It’s interesting to note that with the rivalry between Apple and IBM at its most contentious, and everyone taking sides, which "dashing dairyman" do you suppose a few years later became one of the few earthlings who'd cashed checks from both of them? That’s right, me, the least likely corporate infiltrator you'd expect!

- For contrast, since the next section takes such a deep dive into arch-rival IBM.

- To note that the only company which didn't throw away money on me around the turn of the century is the only company that's even better positioned in 2022. Duh!

I could go on, but this recently unearthed and digitized video of "Compose Yourself," speaks for itself. Enjoy!

{video coming soon}

IBM

Worming my way through two heavily-fortified security checkpoints that screamed “military industrial complex,” I was stupefied that International Business Machines would even consider hiring the same character who’d introduced ritualized milking to the art of stagecraft. The burgeoning PC industry, having exhausted the supply of cookie-cutter geeks, had been reduced to recruiting alternative types, such as yours truly, esteemed author of “Dickheads and Fuckfaces.”

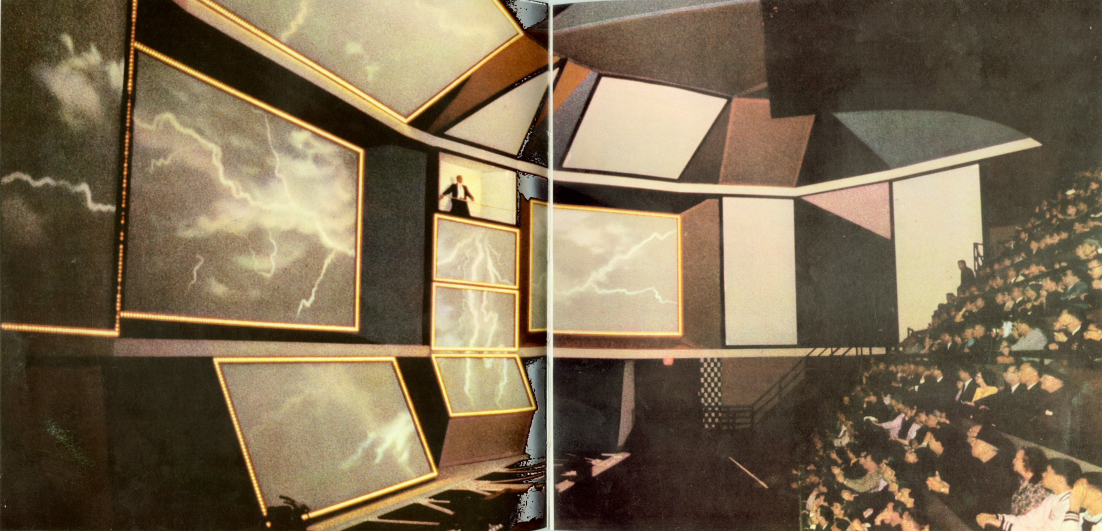

IBM. From the 1960s through the mid-1990s, the computing colossus was the most influential and recognizable PC maker on earth. Its Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen designed Egg Pavilion took the 1964 New York World’s Fair by storm. An audience of 500 fairgoers took their places in The People Wall, a steep grandstand, gasped as it was hydraulically hoisted inside an ovoid precursor to an Imax theater, then had their minds bended by multimedia presentations spread across multiple screens. The message conveyed by IBM's Information Machine was plain: its “idea men” could solve just about any technological riddle you could possibly run past them. Yeah, it was gonna cost you more than the price of a set of studded snows, but if you were seeking a NASA-level partner to launch your growing concern into the Space Age, you knew who to call.

“Coot Lake” was another IBM recollection filed in the “Fond” section of my memory banks. In 1980, I’d stared out at the IBM campus, off in the distance, its bevy of sandstone buildings camouflaged in the grasslands between Boulder and Longmont, while I was skinny-dipping in Coot Lake or sunning along its sandy shores—alongside hundreds of free-love inclined satyrs and nubiles. The scene gained national, er, exposure, after it was featured in Newsweek’s "investigative report" on hedonism in Boulder, catchily titled, “Where the Hip Meet to Trip.” The magazine’s writers described the city as “one giant fern bar, a haven for the counterculture, and a place where “dropouts drop in.” Small wonder I fit right in.

“Coot Lake” was another IBM recollection filed in the “Fond” section of my memory banks. In 1980, I’d stared out at the IBM campus, off in the distance, its bevy of sandstone buildings camouflaged in the grasslands between Boulder and Longmont, while I was skinny-dipping in Coot Lake or sunning along its sandy shores—alongside hundreds of free-love inclined satyrs and nubiles. The scene gained national, er, exposure, after it was featured in Newsweek’s "investigative report" on hedonism in Boulder, catchily titled, “Where the Hip Meet to Trip.” The magazine’s writers described the city as “one giant fern bar, a haven for the counterculture, and a place where “dropouts drop in.” Small wonder I fit right in.

Now I found myself off course, roving the wilds of IBM’s 3,745,080 square-foot campus, attempting to find a mid-manager's burrow situated somewhere in one of ten interconnected buildings on a site the size of LAX.

In the 1990s, in common with most people who already owned or were looking to buy a personal computer, I’d been bombarded with ad agency propraganda that buying an Apple computer affirmed that you were young, hip, and creative—and that owning one automatically made you superior to IBM buyers, who were, in so many words, old, fuddy-duddy, and dull. And oh, by the way, Apple epitomized a paragon of virtue and IBM was an evil empire.

Said demonically effective programming had me doing double-takes when I encountered IBM employees dressed in anything and everything but conservative banker’s suits—which is all I ever saw at Apple. I saw maybe two suits that day, spotted on execs from IBM Corporate wearing orange Visitor tags like my own. The majority of white guys wore golf shirts, Indian and Pakistani guys stood out in turbans and braids down to their butts, Ethiopian dudes said “I’m black and I’m proud” in dashikis and sandals, Asian women carried out their assigned tasks in pleated crepe skirts and silk shirts embroidered with date palms. The “I” in “IBM” was starting to make sense; the Fortune 100 juggernaut was certainly far ahead of the diversity curve.

Everyone I asked for directions seemed really chill, way more than I was, as I hustled down a series of impossibly long hallways connected to other impossibly long hallways, too close for comfort to being late for the big interview. Those extended passageways shared an architectonic feature that was giving me the willies: lined up one after the other, like little honeycomb cells, were a series of puny, windowless, fluorescent-lit closets, I mean offices. None of the doors were cracked open so much as an inch. Occasionally, one opened just long enough to let someone out or in, and I’d catch a quick glimpse of way too many drones crammed elbow-to-elbow, moored to their PCs, staring at low-resolution monitors, getting a good whiff of each other's patchouli and now extinct-for-good-reason aftershaves like Hai Karate. It was hard to imagine that some of the ideas that had changed the course of civilization germinated within these constricted confines.

When I finally found myself hovering outside the office of LeRoy Coleman, an Afro-American middle manager who'd risen up from Denver’s Five Points neighborhood, it took all my willpower to stop ruminating on the IBM Egg, sybaritism at Coot Lake, the odds of becoming the first earthling to collect paychecks from both Apple and IBM, and waking up screaming inside a sardine can. I inhaled from my diaphragm, knocked on the door, heard a deep, "Come in," and stepped inside. The greeting coming from behind a desk could have been scripted by Beckett or Ionescu for The Theater of the Absurd.

When I finally found myself hovering outside the office of LeRoy Coleman, an Afro-American middle manager who'd risen up from Denver’s Five Points neighborhood, it took all my willpower to stop ruminating on the IBM Egg, sybaritism at Coot Lake, the odds of becoming the first earthling to collect paychecks from both Apple and IBM, and waking up screaming inside a sardine can. I inhaled from my diaphragm, knocked on the door, heard a deep, "Come in," and stepped inside. The greeting coming from behind a desk could have been scripted by Beckett or Ionescu for The Theater of the Absurd.

“To be honest, I don’t know why they asked me to interview you or what you’re supposed to be doing here, but Troy isn’t here today,” he bellowed, in a gospely basso profundo.

Existentialism is hard to define, but you know it when you see it. Being supervised by persons who had no idea how or why they were supposed to supervise me was a recurring theme reprised throughout my corporate travels. I'd learn that Troy, presumably my supervisor, wasn't present and accounted for because IBM had ordered him to take some R&R in Cabo, along with his wife and towheaded progeny, since he hadn’t taken a vacation day in three years, he was the department MVP, and they needed him fresh for some momentous-sounding mission classified top secret for the moment.

“I guess I should ask you a few questions about your resumé.”

Fire away. Wait a second—was this a done deal already? LeRoy seemed to be going through the motions. I was getting the sneaking suspicion that I was a shoo-in to be hired for a yearlong contract with IBM. That’s not something that I would have predicted back in the day when I was side-stroking the circumference of Coot Lake sans swim trunks.

After lobbing a few softball questions about all the good work I’d done at Qwest (not!)—which were so basic I was unable to sustain my preferred fantasy that I was a guest on the popular Dick Cavett Show—LeRoy wrapped things up:

“Look, I’m a real hands-off manager. As long you’re doing what you’re supposed to—whatever that is, I dunno—you’ll find me the nicest guy on the planet. But if you mess up, I’ll be all over you like a cheap suit.”

I blinked my eyes at the threatening cliché; faking subservience had never been a go-to option in my emotional repertoire. One emotion I wasn’t faking, irrational fear of confined spaces, kept me from embracing the shock hiring more fully; claustrophobia was making me more light-headed by the second.

“We’re running out of space and PCs,” LeRoy informed me, as if I hadn’t noticed, “but we’ve found a place for you to sit and a PC for you to use.”

Gulp. Images of a sputtering 286 CPU and a ten-year old radioactive CRT monitor with mucous-green phosphorescent dots crossed my mind.

Trailing LeRoy down those elongated passageways, I'd seen the horrorshow hiding behind each and every doorway. The inference that these were the first-call cages and we were heading toward more stopgap solutions was even more worrisome.

Trailing LeRoy down those elongated passageways, I'd seen the horrorshow hiding behind each and every doorway. The inference that these were the first-call cages and we were heading toward more stopgap solutions was even more worrisome.

Boring inside the matrix, LeRoy swiped a card, unlocking a control room of sorts, dominated by a retro array of IBM 360 magnetic tape-based data servers which would have looked right at home on the set of science fiction flicks like Forbidden Planet. With a flourish, he pulled open a solid oak door-within-a-door. Gasp! Adrenaline— manufactured in rapid response to a dire need for self-preservation— surged up my spine. Inside a windowless, oxygenless room, no bigger than a breakfast nook, seven sensory-deprived schnucks kept the home fires burning.

And there it was, an unoccupied place for an eighth, no bigger than the space allotted for a stool at a cramped lunch counter, my own slice of heaven. The silent scream I let out could have been heard in Nepal. Permit me to sum up my state of mind in one word … petrified. No. Can. Do. My conscious mind succumbed to brain lock; fortunately, my subconscious mind was already diagramming a Hail Mary play to salvage the situation. I wasn’t exactly brimming with confidence that I could sell the resourceful suggestion it spit out, but it was the only shot I had.

“I appreciate that you’ve found a spot for me in your rapidly expanding division,” I began, in my most diplomatic tone. “If I heard you correctly, you said that you’re running short of space for workers, and that you’re running out of office computers, as well.”

LeRoy’s face didn’t give much away; maybe I caught a trace of “marginally pleased” that I’d paid attention to his pronouncements and validated them.

“That’s right,” he confirmed.

“Well, maybe I could help things out by … (I swallowed hard) working from home, you know, telecommuting.”

“If I work from home, someone else on our team (corporations love sports analogies) could have this valuable space and this (mismatched) PC and monitor. The PC I built at computer school is a 486 (flying jets at the time). It’s got a 40-meg hard drive (capacious at the time!), and it’s already loaded with FrameMaker and other tech writing software (that I’d smuggled from Qwest and loaded onto my home machine for just such an occasion). I also have a modem and a reliable laser printer (at a time when not everyone did).”

I awaited LeRoy’s reaction, psychologically prepared for a sanitized, corporate version of “Fuck off and die.”

What I heard instead was:

“That’s something to consider. Let me talk it over with Troy.”

Ah, Troy. LeRoy had spoken about the Global Services Division’s absent Golden Boy in glowing terms. When he wasn’t jet skiing, slamming body shots or “otherwise engaged” during his forced vacation, Troy was checking in with the mothership. I knew, because a few days later, word came through that my request to telecommute to IBM had received the department's stamp of approval. Yes! There is a God! What a break! It wouldn’t be the last time my subconscious mind bailed my conscious mind out.

That week was the first of around fifty that I’d bill IBM eight hours a day from the comfort of my own home, bivouaced in an extra bedroom, familiarizing myself with a stockpile of synths, sequencers, and drum machines I'd requisitioned to record an instrumental CD. I was making progress, in baby steps, when the fellow from the recruiting agency that represented me called. Although I was pretty sure he was just checking in to see how I was getting along at IBM, I still got a little antsy—there was no telling how they'd react to the announcement that I was telecommuting.

That week was the first of around fifty that I’d bill IBM eight hours a day from the comfort of my own home, bivouaced in an extra bedroom, familiarizing myself with a stockpile of synths, sequencers, and drum machines I'd requisitioned to record an instrumental CD. I was making progress, in baby steps, when the fellow from the recruiting agency that represented me called. Although I was pretty sure he was just checking in to see how I was getting along at IBM, I still got a little antsy—there was no telling how they'd react to the announcement that I was telecommuting.

“So, how are things going over at IBM?” he asked, matter-of-factly.

“Well, I’m not working at IBM, I’m working from home.” A more accurate statement would have been: “Well, I’m not working at IBM, and I’m not working at home.”

“Oh. Have they got you working hard?”

“Hard as in hardly; I have no idea what the assignment is, and the only guy who can get me up to speed is kayaking in the Yucatán.”

“No problem. Just keep on billing ‘em.”

Sir, yes sir. Whatever you say.

We'd just established there was no issue whether I'd get paid whether I typed a single word or not. But things couldn’t possibly keep slipping through the cracks, could they? Surely a model corporation like IB-effing-M could never be as lax as Qwest, could it? Unlike Qwest, their top execs hadn’t been hauled off in a paddy wagon, their phone booths weren’t being replaced by cellphones, their stock had just soared to an all-time high and appeared unstoppable. I naturally assumed that once Troy returned from Margaritaville, absurd practices like paying contract workers not to write would screech to an immediate halt.

You're gonna wanna watch this!

On paper, that reads like a reasonable assumption, but … they didn't. Back in the coal mine, Troy had a lot of catching up to do. Sorry, he was digging out, no time for a tech writers, but he’d get back to me whenever he could. A week went by. And another. Finally, Troy cleared his power-packed schedule and penciled me in—only to cancel at the 11th hour, explaining that there were “just too many fires to put out.” The fire danger must have been great, since Troy postponed our next three or four scheduled meetings, as well, blaming on the same element.

Two months after I started cashing IBM paychecks, I still hadn’t worked a single second—snapping the previous record I’d set at US West by a good two weeks. My latest unintentional push to set the Guinness Book of World Records for Getting Paid Not to Write was off to a rip-roaring start.

Eventually, the mystery man kept an appointment. Any need to guess at the motivational forces that spurred Troy on was rendered moot once I made myself at home in his golf and grog-themed office. Lit in the soft neon glow of Coors and Rolling Rock beer signs, surrounded by 8x10s of his idols like Tom Watson and Jack Nicklaus grinning ear-to-ear as they donned their prized green jackets after winning The Masters at Augusta, this server savant—who looked like a quarterback and thought like an astro-physicist—gave demystifying the nature of my mission at IBM the old college try.

Eventually, the mystery man kept an appointment. Any need to guess at the motivational forces that spurred Troy on was rendered moot once I made myself at home in his golf and grog-themed office. Lit in the soft neon glow of Coors and Rolling Rock beer signs, surrounded by 8x10s of his idols like Tom Watson and Jack Nicklaus grinning ear-to-ear as they donned their prized green jackets after winning The Masters at Augusta, this server savant—who looked like a quarterback and thought like an astro-physicist—gave demystifying the nature of my mission at IBM the old college try.

The best I could piece things together—which was about as easy as piecing a shredded document back together—IBM Global Services, out of Boulder, Colorado, was determined to build the world’s most extensive “data cloud” (whatever that was) to support “virtual help desks” (whatever they were). Extensive means expensive; they had high hopes that IBM Corporate, headquartered in Armonk New York, would chip in—to the tune of some 50 million dollars. Ah. Silly me, how could I not guess that? Funny, they left that eight-figure number off the online job description. Or maybe I was hitting the bong or something when I skimmed it?

I couIdn’t quite wrap my head around a number like that, but I could put two and two together: the assignment at IBM I’d been hired to successfully complete was writing for fifty million dollars. The audacious number made my ears perk up; the challenge wasn’t entirely without appeal. After all, I really was a persuasive writer, wasn't I—even if up to that point no corporation had shown the good sense to tap into that available superpower. Surely IBM was the exception?

But first, there remained the not insignificant matter of getting up to speed on the data cloud itself. Sounds easy peasy, except that since the project was clearly Troy’s baby, he was the sole conduit to unlock its mysteries. Therein lies the rub: just because Troy had the right stuff to conceive and design the biggest, baddest, boldest and most potentially lucrative project IBM had ever undertaken, that didn’t make him the right guy to break it down for a layman. I sensed, correctly, that even tangential involvement with the writing process gave him the heebie-jeebies.

But first, there remained the not insignificant matter of getting up to speed on the data cloud itself. Sounds easy peasy, except that since the project was clearly Troy’s baby, he was the sole conduit to unlock its mysteries. Therein lies the rub: just because Troy had the right stuff to conceive and design the biggest, baddest, boldest and most potentially lucrative project IBM had ever undertaken, that didn’t make him the right guy to break it down for a layman. I sensed, correctly, that even tangential involvement with the writing process gave him the heebie-jeebies.

But the data cloud of doom wasn’t going to get funded unless some walking, talking combination of T.S. Eliot and Sir Isaac Newton, presumably yours truly, documented precisely what it consisted of in the way of componentry, capability, and scalability—not to mention what sort of ROI the most sophisticated network ever built was projected to generate. Refining the concept would take a year or so, Troy guesstimated, and would have to be documented every single step of the way—which is why I'd been handed that one-year contract.

A subtheme I picked up on is that this network prodigy stood to make out pretty well in the event his brainchild was greenlighted by IBM Corporate. I was perfectly happy to make his dreams my reality. After all, Global Services had already regaled me with an $10,000 endowment to spend as I pleased—like on immersing myself in electronica. On top of that, Troy was down to earth with me, and I liked wallowing in the soft glow of his office ambiance (I forgot to mention the imaginative installation of small-distillery Scotch bottles, separated into Highland Malt, Lowland Malt, Speyside Malt and Campbeltown Malt variants). His lair felt somehow detached from a cold cruel world. So, yeah, I was down to help his young family out any way that I could—which isn't to say it was going to be any less of a bitch.

Over the next weeks, whatever semi-coherent jargon I could leach out of Troy in person or over the phone came out impossibly cryptic. Cryptic, sryptic, after collecting two months’ worth of IBM bucks in exchange for breathing air, it occurred to me that that it might be in my self-interest to produce something, anything, in the way of documentation—if only to justify my continued presence on the payroll. Toward that end, I pored over my sketchy notes and a complex, yet easy-on-the-eyes series of drawings Troy furnished (he was a whiz at creating those in a program called Visio), like a monocled archaeologist deciphering hieroglyphics.

It's a solar fam now; the former IBM campus outside Boulder.

This is as good a place as any to point out that long before and after I roamed the IBM campus, I’d tried my hand at all manner of writing—prose, poetry, lyrics, novels, short stories, journalism, academic treatises and so on—that I justifiably took pride in, and I can confidently state that much, if not most, of it was “up to snuff” (to use a slightly archaic turn of phrase). I tossed in that admittedly haughty self-evaluation up in the express hope of assuring you that self-deprecation isn't my default mode—because the “deliverable” I was about to hand in was, without question, the rankest, rancidest, rottenest drek I’ve ever shown another human being! An assessment like "embarrassing" doesn't begin to hint at its god-awfulness. The only redeemable parts were the powerful technical drawings that I’d liberally pasted in. They were so advanced, they could only have been created by a Vulcan. Or Troy.

Sheepishly, I turned in what I made a special point of emphasizing was a beyond-rough first draft. I waited as Planet Earth's leading data cloud architect thumbed through it, professorially, bracing for the expression of horror that was surely coming.

“This is great!” he enthused. “You’re quite a wordsmith. Let me have a few of the guys read this.”

Huh? Say what? Really? Had he been hitting the Laphroaig 30 Year? I can recollect handing in what I'd hesitantly termed a “report” on a Monday. That Friday, I heard back from my supervisor. He sounded downright ecstatic, as if he’d just holed an ace.

“You’re not going to believe this!”

“I’m not going to believe what?”

“We just got the $50 million from Corporate. Lew Gerstner (IBM CEO) loved it!”

“Loved what?”

“Your report, what else?”

“What report are you talking about? Wait—no way! You showed that rotten first draft to Lew Gerstner?”

“That rotten first draft just got us $50 million. You’re a god!”

Dumbfounded, I would have loved to freeload off Troy’s euphoria, but there was a big question where the grand slam outcome left me—had I just made myself obsolete? Global Services hauling in the fifty mill was beyond comprehension. While it’s true I’d strewn a smattering of psychological selling seeds amongst the steaming pile of dung that passed for a prospectus, unknowable forces had to have informed Corporate more than anything I put in that dopey doc.

“What’s next?” I asked.

“We’ll let you know.” Click.

Then they didn’t. That didn’t deter me from chanting my agency’s “just keep billing ‘em” mantra. As the hours, days, and weeks rolled on, I had to wonder: was IBM just going to keep on paying me indefinitely? It was a long shot, although, based on the strange phenomena I'd already encountered on my various corporate odysseys, by no means was it an impossibility.

For some reason, most people in the 1990s assumed Dilbert was satire ...

Troy did call on me again, right after the seed money had cleared the last bureaucratic hurdle and had been safely deposited in Global Services' coffer. He said he had another job for me, I should come in, he'd fill me in on the details. Sigh. Oh, well—the notion of getting paid indefinitely to not write was more than a little bit far-fetched.

This new “job” would turn out be a patrician proposition—compared to the more pedestrian pastimes I pursued at Qwest. I caught wind of this as we sped away from the IBM campus in Troy’s Corvette C5 Special Edition convertible, his coveted collection of MacGregor clubs rattling in the boot, making a beeline for his slant on hallowed ground —Lake Valley Golf Club. Instead of getting paid to play a goofy niche sport like Nerf basketball, now I was getting paid to play a gentelman's sport enjoyed by kings, rajahs, and caliphs. I was really coming up in the world! Then we were a god and a guru in a golf cart, one of a half-dozen of 'em full of freshly-funded cloud services engineers, downing flasks of the good stuff, Macallan 24-year old, as as we hacked up the innocent course’s fairways, rough, and sand traps.

Wow! Global Services was so over-the-moon that it got the funds it vitally needed in a few months instead of the full year they anticipated, they just kept on paying me for the rest of the yearlong contract. I suspect the logic was as simple as what’s fifty thousand to make fifty million? It didn’t even register to them. No one at IBM or my agency ever said boo. By the end of the contract, I had all the time, money, and gadgetry I’d ever need to record Silicon Rebels to my exacting standards at Coupe Studios in Boulder. The instrumental CD exceeded my high expectations, receiving a fair amount of praise when it came out; it’s a collector’s item now.

Based on what I saw in Corporate America in the 1990s, it was reality!

Silicon Rebels wasn’t an official Milkmen recording, per se, but it was still “instrumental” in prepping my subconscious to conjure up ever more ingenious ploys to source financial aid for forthcoming Milkmen projects that my conscious mind wouldn't have dreamed up in a thousand years. Additionally, that investment in MIDI music production came in handy for fleshing out what had previously been guitar-heavy Milkmen arrangements. Our productions turned more luminous, more “technicolor,” as a result.

Après IBM, my resumé was starting to look stellar; no recruiter or employer would ever suspect that I’d failed upwards like five times in a row—or that I’d been paid for something like 3,000 hours when I’d actually worked maybe 120. Now I could pass myself off as a Senior Technical Writer, get paid twice as much, and really sock away some dough.

The next (unintentional) victim, I mean (inadvertent) benefactor, on my list was none other than Intel Corporation, riding high after selling half a billion CPUs in the dawn of the information age, but currently rudderless after founding father Andy Grove passed away.

Intel

I was sitting on a chunk of coal colored lava outside an adobe earthship, a Taylor 612C on my knee and metal fingerpicks affixed to my right thumb, index and middle fingers, rehearsing the Travis picking part to “World Without Dreams.” The sacred mountain loomed in the distance, lording over Pueblo Indian lands. In the foreground, a mayordomo and his crew were clearing out acequias— a series of primitive man-made ditches used to irrigate farmlands—the traditional way, with hand tools. Liking what I was hearing, I carried my six-string inside. Surveying all the recently acquired gear in my makeshift yet mighty studio, I positioned a Rode Classic mic in front the Taylor, took a deep breath, and pressed Record.

Four and a half minutes later, I played the track back, expecting to be elated with the results. Instead, I was astonished to discover at least three dozen mistakes and a bunch of loud pops where the metal picks had inadvertently struck the spruce top. Those tiny mishits sounded like thunder. It occurred to me that during a four-and-a-half minute fingerpicking song, with those three fingers in constant motion, a guitarist strikes the strings over two thousand times. Even if I played the part 98% perfectly, dozens of retakes and corrections were required. Oh. Funny thing about that! It was hard to miss the conclusion: there’s a huge difference between what sounds good sitting on a rock and what sounds good on a recording you’ll be listening to for the rest of your life. I also realized I couldn’t have picked a harder part to tackle right out of the gate! Huh. This was going to take a whole lot more time, effort, and focus than I’d ever imagined.

By 1999, I’d banked enough “fuck you” money to record a CD in an inspiring locale of my choice—preferably one that put some physical distance between myself and the prying eyes of my about-to-be-estranged wife and her two-pronged plan for self-improvement (mine): 1) become a full-time, uncomplaining, wage slave like her and her yuppie friends; and 2) stop whining about spending all my not-so-hard-earned money on home remodeling—and none of it on home recording.

By 1999, I’d banked enough “fuck you” money to record a CD in an inspiring locale of my choice—preferably one that put some physical distance between myself and the prying eyes of my about-to-be-estranged wife and her two-pronged plan for self-improvement (mine): 1) become a full-time, uncomplaining, wage slave like her and her yuppie friends; and 2) stop whining about spending all my not-so-hard-earned money on home remodeling—and none of it on home recording.

Practicality is not, in and of itself, an attackable concept, but I’d already leaned so far in that direction, I was about to keel over. Taos, New Mexico, 315 miles away from Boulder, Colorado, beckoned from afar. The scenic tricultural (American Indian, Hispanic, “White People”) community was far enough away, yet close enough—about a four hour drive away, back in the days when I’d think nothing of racing 100+ MPH through the middle of nowhere and a speeding ticket only cost $75—to check a lot of boxes.

Two natural features demanded attention: the Taos Gorge, almost as awe-inspiring as the Grand Canyon—particularly if you hiked one of the trails leading down to the bottom of it with llamas and a guide or took a balloon ride through it—and Taos Mountain, jutting majestically out of sacred Indian lands. Somewhere up there was Blue Lake, the mystical wellspring no white person had ever visited or was ever likely to. Concealed by a stand of ancient cottonwoods, the Taos Pueblo, still inhabited after 1,000 years, was the most recognizable Native American structure in the American West, an artist and photographer’s staple.

I settled into a fabulous adobe abode overlooking a sea of sage and pinion-dotted Indian lands. There was something particularly virile about the volcanic soil. Sunflowers regularly hit twenty feet and hollyhocks came close. The night sky humbled the great planetariums, especially with a full moon rising over the crest of the Sacred Mountain. Gazing out into infinity emphasized just how small my imagined problems were, in comparison with the enormity of the cosmos. The tiny hamlet of Arroyo Seco, within walking distance of my casita, was far, far away from the land of the cubicles, far, far away from the chain stores uglifying the suburban highway interchanges encroaching on my acreage in East Boulder, far, far away from the cares of the world. In other words, Arroyo Seco’s fertile environs couldn’t have been any more ideal for cultivating creative projects.

Before I could tap into that energy, assimilating a new PC, a Soundscape SSHRR1 Digital Audio Workstation (which eliminated the need for tape recorders), and a lineup of unfamiliar studio gear was going to take a whole lot of woodshedding. That wasn't going to happen overnight; user documentation hadn’t really taken a great leap forward; user forums were still in their infancy. Getting the hang of how it all worked as well as experimenting with where each piece should be positioned within easy reach was some tough sledding. I kept at it, though, and, after a lot of trial and error, I was getting acclimated to wearing multiple hats—engineering, performing, arranging, producing, writing, editing, etc.— at once.

Before I could tap into that energy, assimilating a new PC, a Soundscape SSHRR1 Digital Audio Workstation (which eliminated the need for tape recorders), and a lineup of unfamiliar studio gear was going to take a whole lot of woodshedding. That wasn't going to happen overnight; user documentation hadn’t really taken a great leap forward; user forums were still in their infancy. Getting the hang of how it all worked as well as experimenting with where each piece should be positioned within easy reach was some tough sledding. I kept at it, though, and, after a lot of trial and error, I was getting acclimated to wearing multiple hats—engineering, performing, arranging, producing, writing, editing, etc.— at once.

With no one else around to take up the slack, I began recording all the instruments and vocals myself. That included bass and drums. Faking an entire drum kit on a MIDI keyboard (Alesis Quadrasynth Plus Piano) was doable, although it was a grind—but that’s what artists did in Taos, they ground out art, the noblest human endeavor in my book. I felt unfettered and alive, to quote one songstress, at one with time and space, responding really well to life in a gallery-filled town that was basically one big arts colony.

It was big news when Milkmen co-founder Steven Solomon joined the fray. He began making regular pilgrimages down from Denver to escape his own domestic, er, challenges. That upped the ante exponentially—at long last, The Milkmen were recording again, after a, sheesh, fifteen-year absence! All was right with the world! Natural order had been restored.

It was big news when Milkmen co-founder Steven Solomon joined the fray. He began making regular pilgrimages down from Denver to escape his own domestic, er, challenges. That upped the ante exponentially—at long last, The Milkmen were recording again, after a, sheesh, fifteen-year absence! All was right with the world! Natural order had been restored.

We were methodically working away, track by track, song by song, relentlessly going about the business of recording the collection of tunes that ultimately became the Dairy Aire album. Suddenly, the assembly line ground to a halt, interrupted by a call from a headhunter. That wasn’t unusual, I was in high demand—I mean, who wouldn’t want to hire a top gun tech writer who’d already pocketed six figures for pecking out maybe two readable sentences over a three-year period, right? With little appetite for more Theater of the Absurd, and with fortune smiling down on us in the digital recording domain, I’d been blowing off all tech writing gigs. This one, however, took on a life of its own. We join the call just as it was getting interesting ...

“So, how’d you like to work in Salt Lake City?”

Hilarious! What delicious jest! Luring me to the land of the Latter Day Saints (LDS) was never going to happen, but this Lorraine Rougement had an undeniably sexy name and a very seductive voice. I played along for a lark, impressed with her detective work; after all, she’d tracked me down in Arroyo Seco, NM, population 1,385.

“Why would anybody want to do that?”

“Because we pay more. Not everybody wants to come to Salt Lake City.”

“You don’t say?”